Essay

In Defense of the Humanities

Feb 19, 2022

There is no doubt in my mind that the first argument against the pursuit of the humanities emerged as soon as humans could wield primitive tools. “Why waste your time sculpting this ivory tusk when you could help us hunt, or create tools to help us plant seeds?” says the theoretical caveman to his idealistic brother.

Surely, there is some ancient philosopher who tells us of the value of studying the humanities. If I were well-read in philosophy (re: a discipline within the humanities), I would be able to answer your question quickly and carry on with the rest of my day. But, because I don’t have that level of cultivation, what I have to concern myself with here is constructing an argument that can, once and for all, quell the pragmatically-minded who think that humanities are “nice” and “interesting” to study, but offer no value to the modern world.

Why, they say, should we bother ourselves with obscure historical events, with the figures of a Renaissance painting, with the word order of an aboriginal language, with the poetry of Islamic polymaths, with anything, in short, that has no practical value in today’s society? Wouldn’t the time and minds of our brightest young folks be better spent in tackling the “real” challenges of today: climate change, technological innovation, medical research, and the like?

In fact, there are two arguments here.

1. You can’t make a living off studying the humanities

The first is the economic one. Assuming for a moment that the humanities are interesting and useful, unfortunately, studying them doesn’t accelerate the process of finding a well-paying job, so in fact they are not “worth” pursuing. In developing societies where the emerging middle class is built on daughters and sons obtaining irrevocable professional degrees (via medicine, law, and engineering), then it is true that the poor cannot sustain themselves on literature or art alone. In some cases they may become performers or highly successful artists, but this is in creating or performing an art, not studying it per se.

However, for at least a century in the developed world, and today in large cities across the developing world, anyone with a humanities degree can apply for the same companies as the engineers, lawyers, and doctors, in adjacent departments. If one is capable and hardworking, she or he will rise to managerial status and be able to live a comfortable life, albeit at a slightly slower pace than the ones with the more lucrative professional credentials. But, in the end one can expect a reliable salary, and in cases of high capability and strong work ethic, even a luxury life.

2. The humanities are not “useful”

The second argument is a philosophical attack on the value of humanities. When people say the humanities are “useless”, what are they actually referring to? That is, how are they defining utility? My interpretation of their usage of “useful” is something that serves society, preferably directly. For example, being part of the team that cures a disease, signs into law human rights, invents phones that connect the world instantaneously. But, let me ask you:

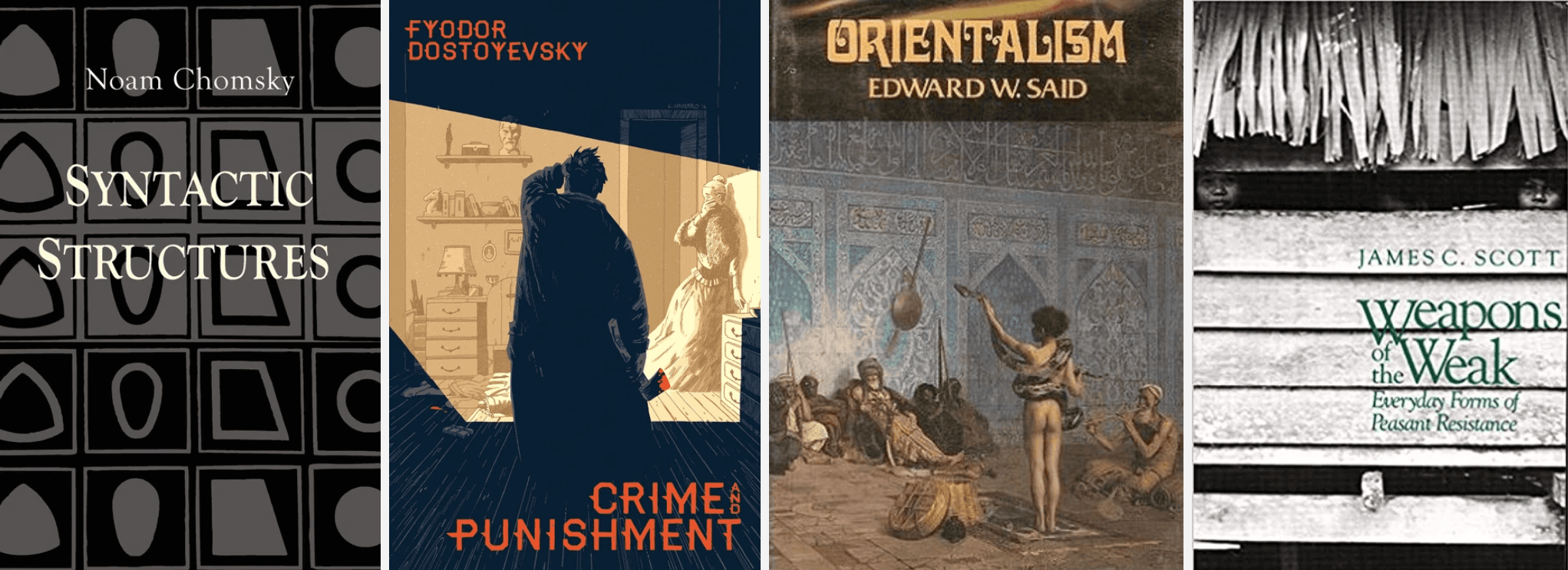

If I write a novel, like Dostoevsky, that reveals the inner part of the human psyche which no psychologist or psychoanalyst has been able to explain scientifically, is that not useful?

If I uncover, like Edward Saïd, how the portrayal of Easterners in French and British 19th century painting casts a romanticized, Western view on the Orient, and that this gaze still persists when we make laws and treaties with the Modern Middle East, is that not useful?

If I find, like Noam Chomsky, native speakers’ biologically innate language faculty, and get one step closer to unlocking the mystery of how the human brain differs from animal brains that cannot sustain language, is that not useful?

And finally, if I uncover, like James Scott, the secret lives and languages of the oppressed, and thereby reveal the motives and desires of a nation’s people unfiltered by the view of the aristocrats and governments that seek to rule them, forcing us to re-evaluate our understanding of what it means to be governed, is that not useful?

All in all, although there is clear value in humanities’ external applicability, where it differs from and adds greater meaning to our lives is in its ability to force us to look inward, to ask the big questions: Who are we? Where do we come from? What do we want out of this life? Where is our society going next?

So, the next time someone asks me why I study the humanities, my response will simply be, “Because I’m curious about what it means to be human.”

More in

Essay

Liminality

Jan 10, 2025

How to connect the divided opinions on ChatGPT

Feb 23, 2023

A guide to protestors' chants

Oct 21, 2022

Consejos para jóvenes postulándose a un trabajo

Feb 17, 2021

Quelques Réflexions sur le Salaire

Dec 24, 2020

Why start a blog?

Aug 29, 2020

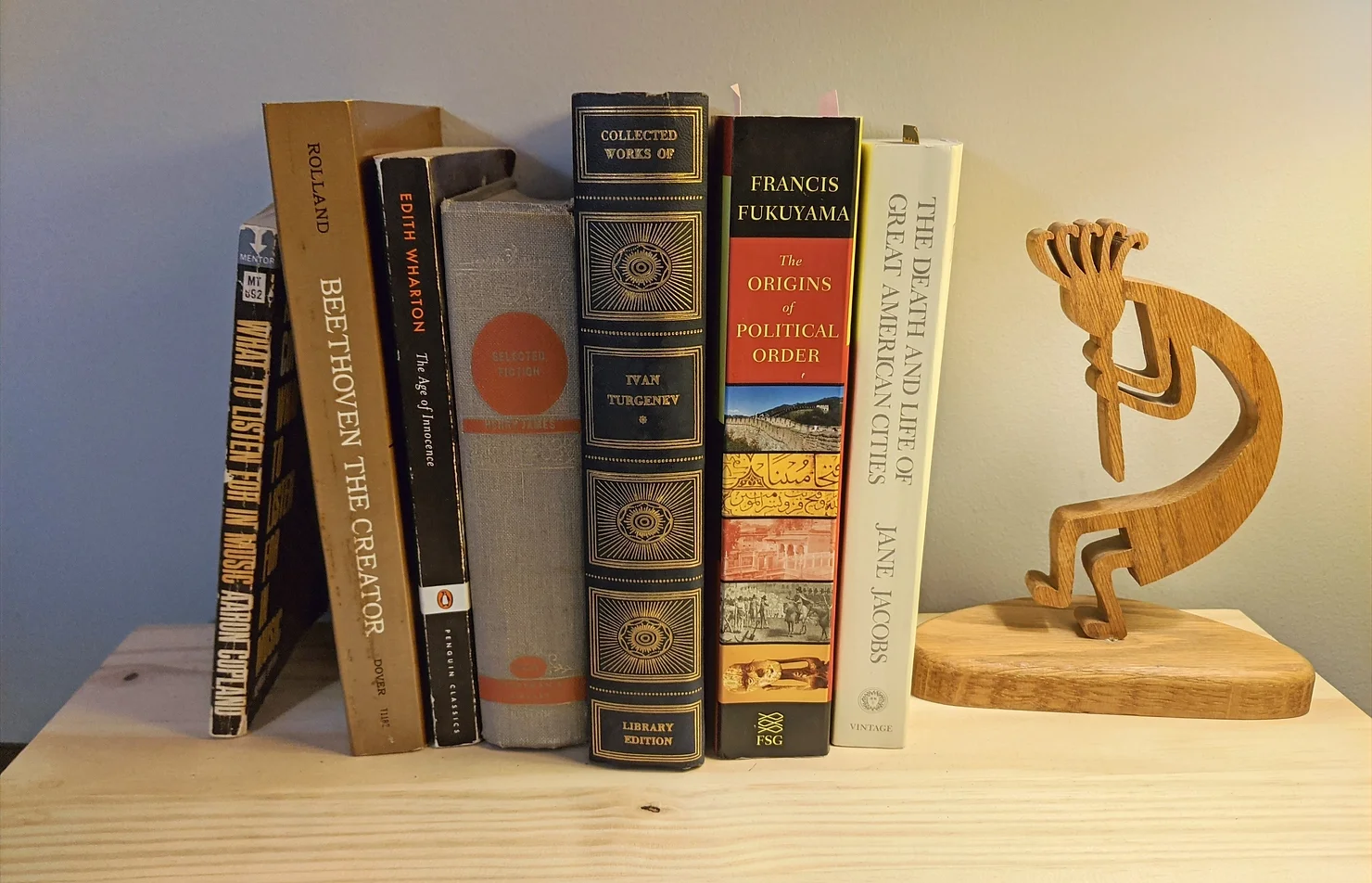

A First Blog Post: Pandemic Books and Blues

Aug 2, 2020